An Introduction to Early Jewish Life on the Island

Museum of the Snoa.

Goedendag! Ik heet Ester Jesurun-Henriquez

Good day! My name is Ester Jesurun-Henriquez. I was born in 1775 on the beautiful island of Curaçao. My mother was Debora Israel St. Cruz and my father was Moses Henriquez. Curaçao is in the southwestern part of the Caribbean, only about 40 miles off the coast of Venezuela. Curaçao means “heart” in Portuguese, and for many, many years our island has been the heart of the Dutch Caribbean.

Before European colonists arrived, the island was the homeland of the Caquetios, an Arawak people. When conquistador Alonso de Ojeda arrived in 1499, there were about 2,000 Caquetios living on the island. The Spanish cruelly enslaved many of the Caquetios and shipped them off to the island Hispaniola. In 1634, the Dutch decided to lay siege to Curaçao, and took the island away from the Spanish to use as a harbor. The lack of water and dry climate made the island ideal for making salt from sea water. Salt was necessary for making both herring and salted beef that people could eat on journeys. Salt fetched a good price.

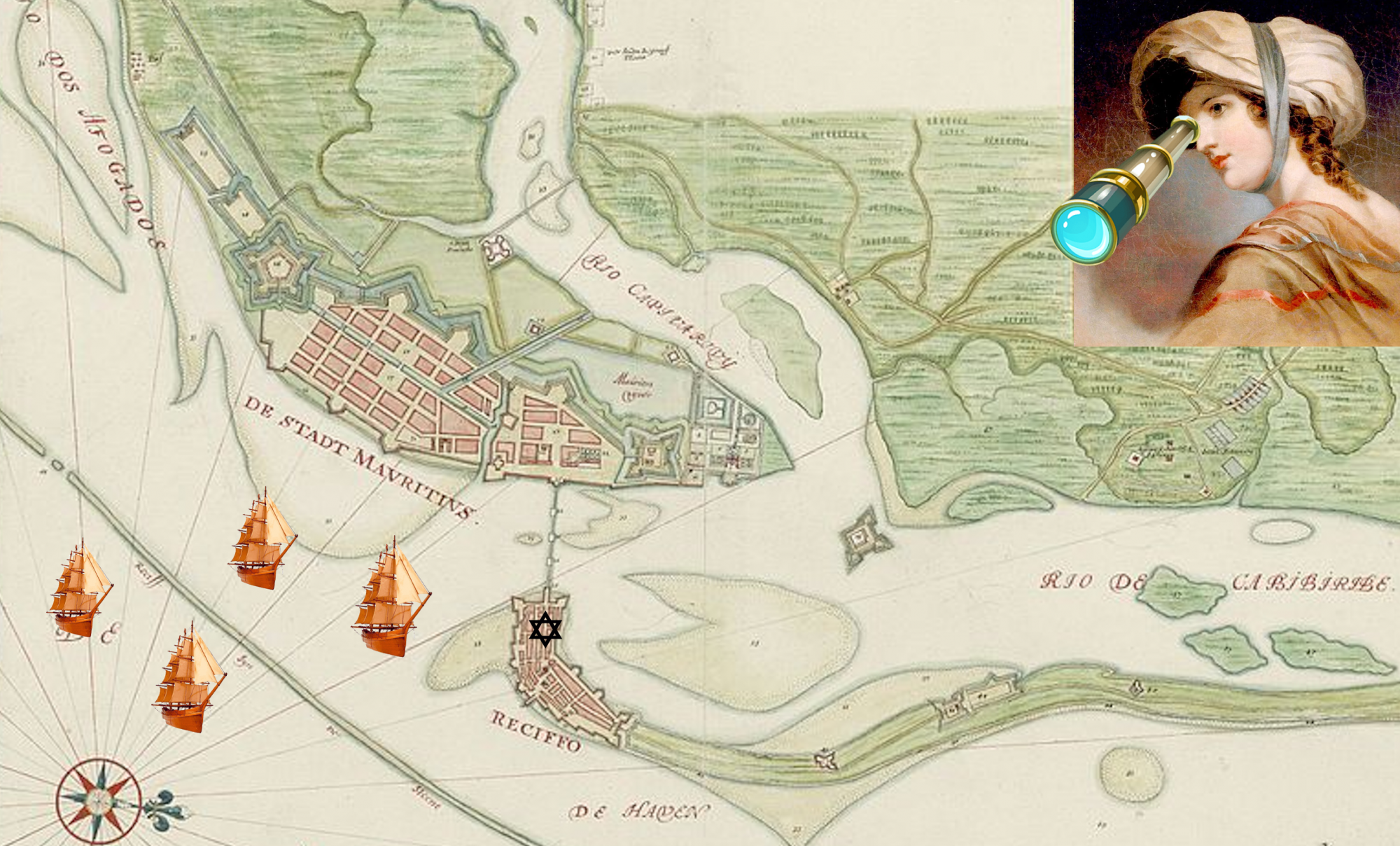

With the arrival of the Dutch, the Jewish population of Curaçao grew, particularly after the arrival of Jewish refugees from Recife in 1654. Although some plantations were set up for indigo and other products, the main business of the island was trade. In 1674 the island became a free port, open to all traders and free from customs duties. Soon the island became one of the wealthiest places in the Caribbean. At our peak, the Jewish community was about 1500 souls, or roughly half the white population of the island.

Like most Jews on the island, I grew up in the old Punda neighborhood near the Snoa, the Portuguese synagogue. Our congregation was named Mikve Israel–the Hope of Israel. The synagogue I attended was built in 1732, long before I was born. The congregation had begun in 1659, and this was our sixth building. Each time our congregation grew, we built an even bigger and more beautiful structure. As in other Caribbean synagogues, the men sat downstairs and the women in the balcony. As time went on, other synagogues would pop up in Otrobanda and Scharloo, but none had the staying power of the Snoa.

Even though it is our sixth building, the Snoa is the oldest synagogue in the Americas that has been continually used ever since it was built! The design is modeled on the Esnoga in Amsterdam, which helped start our congregation. In the synagogue complex were also a school and house for the Rabbi and his wife, and a mikveh. Our school trained many of the rabbis for congregations all over the Americas. Over time, our congregation grew so powerful that we became the “Mother Congregation of the Americas.”

In 1796, I married Abraham Jacob Jesurun, from one of the oldest families on the island. We had seven children who married into many of the island’s important Jewish families. Although Abraham and I owned plantations, most of our money came from trading along the wharves near the synagogue. My husband was a powerful merchant and by his death, he was one of the wealthiest men on the island.

Much of Jacob’s business was in nearby Venezuela, but he also traded with people in Santo Domingo and other places in the Caribbean. Many wonderful goods arrived overland in Coro through the Andes, and trade with Venezuela became so important for people in Curaçao, that some families established a small Jewish community in Coro, Venezuela. Some of my children bought houses there. The Coro community had its own synagogue, cemetery, and mohel. Recently archeologists also discovered the remains of an early mikveh in the house belonging to our son Moses’s in-laws, the Senior family.

Although my husband Jacob was only nine years older than me, he died thirty years before I did, so I was a widow for much of my life. When he died, his real estate was worth 57,575 guilders, a princely sum.

Interested in how much a guilder was worth? You can calculate guilders (fl.) to Euros here and Euros to dollars here.

The Dutch protected the rights of women more than other empires. In the British colonies, women lost control of what they brought into a marriage, but Dutch laws favored widows more, and my ketubah (marriage contract) also helped protect me. After my husband died, I split my time between our house in near the synagogue and our country house on a plantation called Ronde Klip (“Round Cliff”), one of the largest estates on the island.

I also had other landhuizen (plantation houses) across the island such as Bottelier, Cerrito (“Small Hill”), Rist en Vrede (“Rest and Peace”). Unlike many Caribbean islands or the Southern United States, Curaçao was too dry to grow crops that would bring in a lot of cash, such as sugar cane, cotton, tobacco, or coffee. Instead, people mainly used plantations to raise food and livestock to feed people on the island.

The man who owned Ronde Klip before us was named Joseph Capriles. When he owned Ronde Klip in 1798-1807, he had 1,000 sheep, 101 cows, 6 horses, and 12 donkeys. These animals ate so much they left the land bare in places and made it even harder to feed animals. Thus when my daughter-in-law Sarah Senior Jesurun ran the Ronde Klip estate in 1855, she had fewer animals: 352 sheep, 87 cows, 2 horses, 48 donkeys, and 254 goats. The goats were hardier than the sheep and could eat almost anything.

Revolt of 1796.

These animals did not raise themselves. Even though I owned the plantation, I did not feed or care for the animals. Instead fifty enslaved people lived on Ronde Klip took care of them. By the time my daughter-in-law was running the estate, she had sixty nine enslaved people to care for her flocks and house. This number may seem large, but is quite small compared to the amount of people who would have been forced to work on plantations in the Southern United States. The lives of enslaved people in Curaçao, however, were probably just as hard. No one wanted to be a slave. In 1795, an African man named Tula led a revolt of around 1,000 rebels who wanted to end slavery on the island. It would take almost another sixty years, however, until everyone was free. Today there is a statue celebrating what Tula tried to do.

Just because people had left Africa and were denied their freedom didn’t meant they had left their culture behind. The kidnapped slaves brought with them languages, stories, music, religion, dance, and even a special way of making houses. The enslaved people on Ronde Klip lived in small cunucu houses surrounding the large landhuis (plantation house). Cunucu houses typically had a thatched roof made from corn stalks and sloping adobe walls. Enslaved people also innovated with what was available on the island, adding cactus for fences. You can see gallery below of what a house built in this style looked like. The cunucu house below is about 120 years old and is now a museum. The man who lived was named Mr. Scoop and he was much better off than the enslaved people who lived in plantations during the era of slavery.

Landhuis & Cunucu

Cunucu

Floor plan

Mr. Jan Scoop (1907-1989), born and lived in this house

Table

Straw mat for sleeping

Kerosene Table Lamp

Kitchen

Historic Pots

Grinding stone

water storage

Oven

Wash board

Freedom Proclamation of 1865

Slavery was abolished on the island in 1863, but conditions were still very hard. People like Mr. Scoop continued to live in cunucu houses. You can see that he took pride in his house and worked to make it clean and beautiful. The names of many of the families that lived and worked on the plantations my family owned are preserved today in the island’s slave registers, which will soon be searchable online.

Just like the people from Africa, we Jews who came from Iberia and Europe also brought our religion and culture with us. We kept our records and listened to sermons in Portuguese. We sang songs and wrote poetry in Hebrew and Spanish. We made beautiful gravestones carved with figures from the Hebrew Bible. We told our own lives through bible stories. Moses who brought our family to the island from Spain was like the biblical Moses who led the Jewish people out of Egypt. Mordecai who rescued us from the French Pirate in Curaçao, became Mordecai in the story of Purim, and so on.

Jacob’s Ladder

Symbols of Death and

Cutting down the Tree of Life

David, Abraham, and Rabbi Aboab

A Deathbed Scene

Gravestone of a Merchant

Washing the Hands of the Cohenim

Mordecai in the Story of Purim

Elijah and the Holy Merkabah

In the second half of the nineteenth century, many Jews found the Punda neighborhood in Willemstad to be too crowded, and moved across the inlet to a neighborhood called Scharloo where it was cooler and more comfortable. Those who wanted to do so could still walk to the Snoa, but also a small synagogue opened up in Scharloo for the Ashkenazi Jews.

My children did quite well for themselves. My son Jacob (named for his grandfather) was known as the “Curaçaoan Rothschild.” Another of my sons was a doctor who helped people. Like many people at the time, my sons lived in Scharloo as well as Coro. In 1858, my son Abraham Jacob Jesurun bought La Mararvilla (“The Marvel) on the main street in Scharloo at 172-174 Scharlooweg (“Scharloo Way”). It cost 8,000 guilders–as much as a ship in my day.

Activity

Sopi di Galina

Equipment

- Crock Pot

Ingredients

- 1 whole chicken cut into 8 pieces (or you can use a pack of 2-3 chicken leg-quarters)

- 2 limes

- 3 stalks celery sliced crosswise into half moons about 1/4 inch thick

- 2 large green peppers (or one red and one yellow if you are allergic to green peppers). You can do small chunks or 1/4 inch slices.

- 1 small onion cut into quarters and then thinly slice.

- 1 clove garlic minced

- 3 large carrots sliced

- 2 stalks green onions washed and cut into circles about 1/4 inch wide

- 2 medium tomatoes cut into chunks about 1/4 inch square

- 2 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 pound beef bones don’t omit these if you can help it. They really add a lot of flavor to the soup

- 3 bouillon cubes (Telma cubes are perfect or you can use Osem beef flavor. If you use the powder, add 3 teaspoons. Don’t have beef flavor? You can )

- 4-5 medium potatoes peeled and cut into bite sized chunks

- 1 cup vermicelli the small egg noodles they have in the kosher section are perfect

- 1 can (16 oz.) “whole corn kernels” or two corn cobs with the kernels cut off

- 1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce optional, but if you keep kosher I recommend Haddar brand as it is both kosher and vegan (fish free). This is a flavor that was added to a lot of old Sephardic recipes.

Instructions

- Place beef bones in bottom of large Crock-Pot.

- Rub chicken with limes and add leftover juice and chicken to Crock-Pot.

- Cut celery, peppers, onions, garlic, carrots, green onions, and tomatoes and place on top of chicken.

- Add tomato paste and bouillon cubes Add just enough water to cover chicken, vegetables, and bones.

- Cook on high in the Crock-Pot for about 4 hours.

- Discard soup bones. Remove and cool chicken on a plate or bowl. When cool, de-bone and de-skin the chicken and cut or shred into large bit-sized chunks. Keep chicken chunks for later and throw away bones and skin.

- If you don’t like vegetables, you can remove all but the carrots at this point.

- Add potatoes and corn to Crock Pot. Replace lid and cook on high for about 1.5 more hours.

- When potatoes are nearly done, add vermicelli, and return chicken to the Crock-Pot for 20-30 minutes.

- Add Worchestershire sauce to spice the soup if desired

- If you are making the soup on Friday and want to keep it warm for Shabbat dinner, turn soup to “warm” in the Crock-Pot and it will keep nicely until dinner.

Quiz

Learn More

The following people lived at least part of their lives in Curaçao: