Hallo–Goedendag! Aangenaam. Ik heet Maria Louisa de Hart.

Hello–good day! Nice to meet you. My name is Maria Louisa de Hart.

This is my husband Johannes Ellis. This portrait was taken of us in 1845 just after we were married. I was only nineteen when the picture was taken. It is an early kind of photography known as a daguerreotype. Early on, it would take 60-90 seconds for the picture to fix so you had to sit very, very still. Recently this photo has become quite famous, as it is the oldest known photograph from Suriname!

My husband Johannes was born in Ghana on the Gold Coast of Africa, but I was born in Paramaribo, the largest city in Suriname. I lived there most of my life, so I am very qualified to tell you about it. Although sometimes Suriname was owned by the British, when I was born in 1826 the colony was Dutch. My father was a Jew named Mozes Meijer de Hart. He came to Suriname around 1810, but Jews had been in Suriname long before that.

After the explorer Alonso de Ojeda “discovered” the coast of Guyana in 1499, King Philip II of Spain claimed the territory for himself. Of course many people lived here before that and considered the land their own! Even today there are about 12,000-24,000 indigenous people in the country. Some of the largest communities of first peoples were the Caribs, Taruma, and Sapoyes. One of the first things Europeans did was try to set up trading posts, but they weren’t very successful as the people who lived there fought back against the invaders.

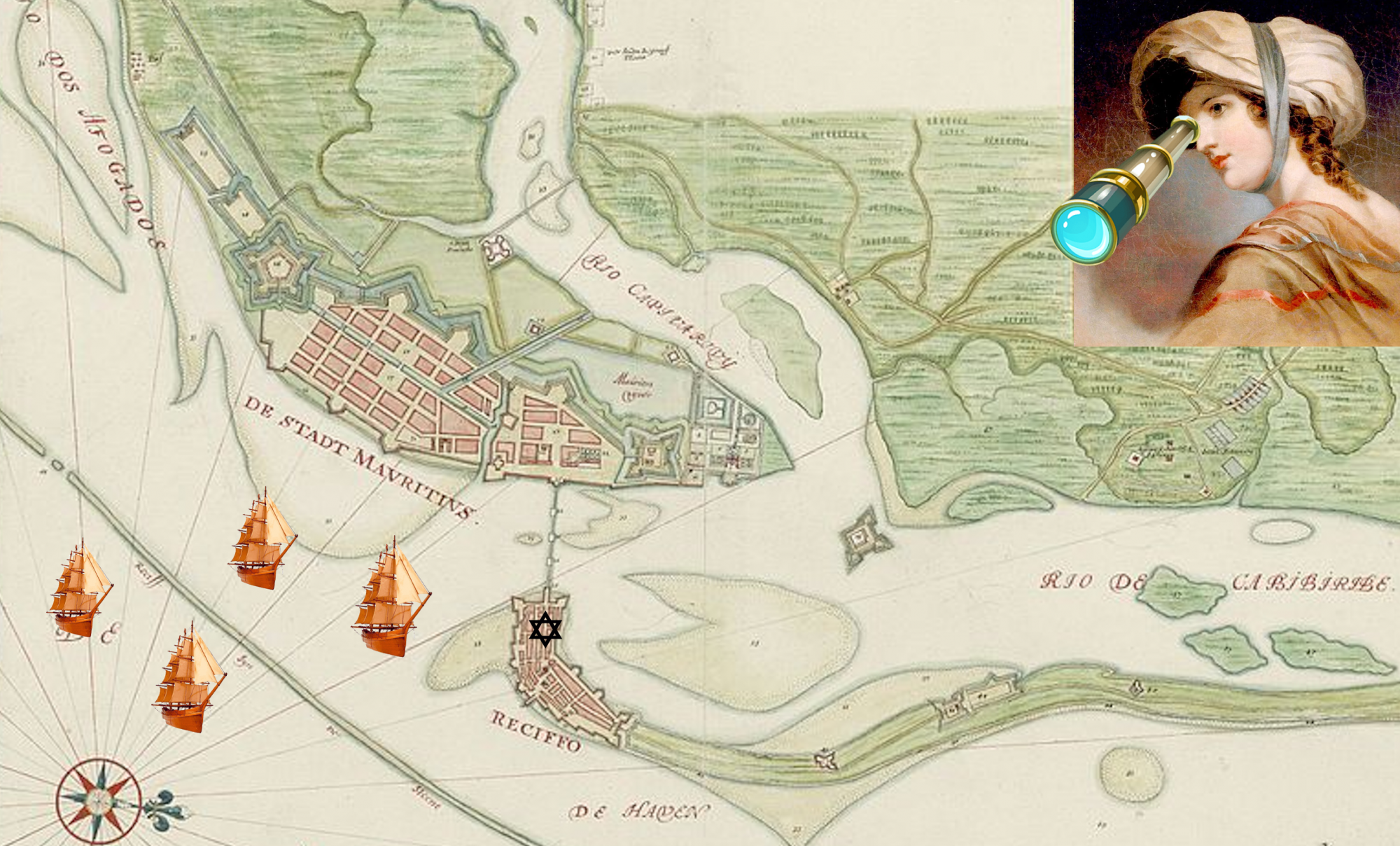

In 1650 the British made a deal with the Carib kings, who agreed to allow a settlement. Soon afterwards, a hundred British planters arrived from Barbados to set up sugar plantations. They kidnapped and bought enslaved Africans to work the fields and process the cane. According to Jewish historian David Cohen Nassy, Jewish settlers arrived a couple of years later. In 1667, the English gave the colony to the Dutch in exchange for New Amsterdam (New York). That may seem like a bad deal for the Dutch, but at the time it was a steal! Suriname was a wealthy sugar plantation, and New Amsterdam wasn’t much of anything yet. Already by 1667 there were at least six Jewish plantations along the Suriname River in a town called “Jodensavanne”–Jews’ Savannah.

Jodensavanne was the first Jewish town in the Americas. Jews designed the town and placed the synagogue at the center. They called it Berakha be Shalom (Blessings and Peace). By 1694, more than 570 Jews lived in Jodensavanne along with 9000 enslaved people worked in the fields. At its peak there were over 2,000 Jews on 115 plantations in the area. Upriver from Jodensavanne was the main port of Paramaribo. This was home to two synagogues: Zedek ve Shalom (Portuguese) and Neve Shalom (High German or “Ashkenazi”).

My father Mozes Meijer de Hart was born in 1793 in Amsterdam, to Ashkenazi parents. He came to Suriname around 1810 and bought the Sardam sugar plantation and Bodenburg coffee plantation. There, he fell in love with my mother Carolina Petronella van de Hart who was one of the enslaved people on the plantation. He freed her and married her. They had twelve children (including myself) and lived in a beautiful house at Waterkant, along the waterfront.

Although my mother chose never to convert to Judaism, she could have. The Surinamese Jewish community was very diverse: by the time I was born about 10% of Surinamese Jews had some African ancestry. Surinamese Jews with African ancestry weren’t always treated very well, however: they made us sit in the bad seats, we couldn’t have synagogue honors, and we even got buried in the swampy section of the cemetery. Finally, in 1770s we got fed up and established our own congregation called Darhe Jesarim (Path of the Righteous) with their own building on Sivaplein.

Sadly Darhe Jesarim didn’t last long. The “white” Jews resented Darhe Jesarim and in 1800 the synagogue was destroyed. Once again Jews of color had to attend one of the other synagogues and follow their oppressive rules. Today, those divisions are gone and everyone who is a Jew is just a Jew. By the time I was married things were already starting to change in Suriname. My husband’s mother was also partially African, but my husband became captain of the Surinamese militia. Like my father and mother, Johannes and I were quite wealthy, even though I was born a slave. Our house was on Keizerstraat right by the “High German” Synagogue.

In 1860 Johannes and I moved to the Netherlands, and eventually our son Abraham George Ellis became a Vice-Admirable and Cabinet member. Some of the beautiful houses we lived in in Amsterdam include Weesperzijde 14, Marnizkade 13, and the glorious Herengracht 173. Some of my descendants are still alive. They donated my portrait and other family photos to the Rijksmuseum, one of the fanciest art museums in the Netherlands.