Teaching about slavery is painful but important. If your ancestors were enslaved, the need to talk about slavery most likely seems utterly obvious. It’s a history that is raw and very, very real. If you are a white Jew, however, tackling slavery might seem risky. For many years, historians who wrote or taught about Jews in early America tended to ignore or downplay or the issue of slavery, sometimes out of fear that talking about Jews as slave owners would lead people to hate Jews more. What happens though, we ignore an uncomfortable past? How can we teach about Jews and slavery in a responsible way?

First, why do we need to talk about slavery at all? Imagine if you were in a class that talked about World War II, but barely mentioned the Holocaust! Even worse, what if every time you brought up the horrors of Concentration Camps, and your teacher referred to them as “detention centers” and insisted her ancestors who worked at those centers were always kind to Jews. “They were good Christians and gave them Sundays off,” your teacher explains. When you object, she plays you some zimrot that Jews sang while they were there. “Sure, there were some people who treated Jews in the centers poorly,” your teacher says, “but they were just bad eggs.” Would you feel infuriated? Most likely. Would you be worried if the other students in the class nodded their heads and took in this version of events as facts? You bet. [Sound far-fetched? See my notes below]

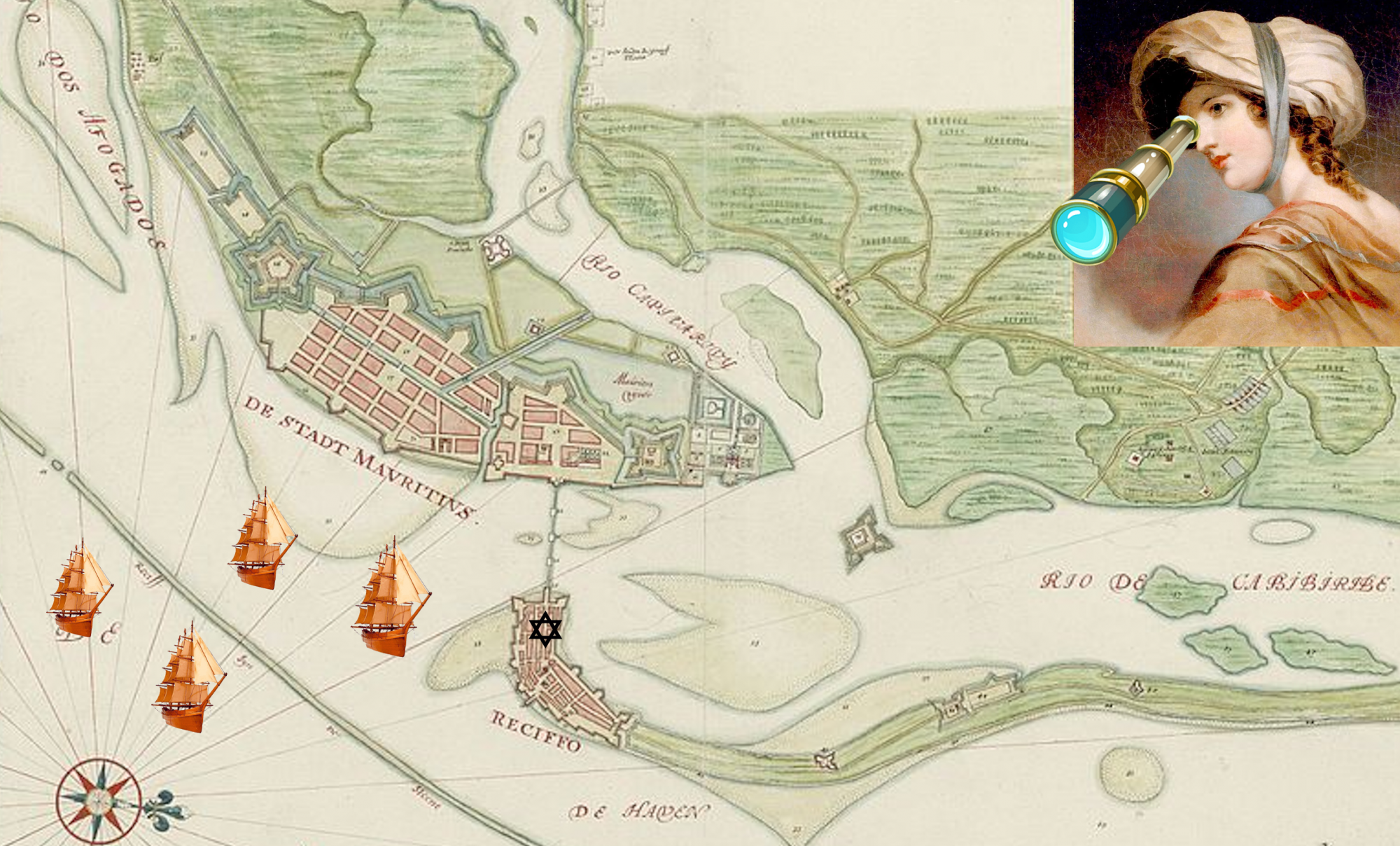

One reason you would feel irritated at your teacher’s understanding of history is that Holocaust wasn’t about a few mean people, but about a system of oppression. When UNESCO explains why we need to teach about the Holocaust, they emphasize “Education about the Holocaust is primarily the historical study of the systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators.” The same is true when we teach about slavery in the Americas: slavery wasn’t about a few evil people, but about the “systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution” in which millions of people were captured and placed into forced labor camps. The people running these camps called the labor camps “plantations” and wrote books or painted pictures about how great life was for everyone on them. Those images showed plantations as a sort of productive, pastoral bliss and ignored the pain they caused.

the South perpetuates the idea that

enslaved people sang because they

were happy.

Even after the labor camps became illegal, many people continued to use the term plantation in a romantic way and created films, books, images, and even children’s cartoons that romanticized life for the people enslaved on them. Imagine if Disney had created a cartoon about how great life was for the people in concentration camps and how the Nazis were trying to help them. This is how many people feel about Song of the South, a story which still gets celebrated at Disneyland today in some of its rides! Now imagine that every time you went to the grocery store there were brands of food that showed Jews happily working in concentration camps, all as a way to sell German products. Personally, I would start to find even going to the store or picking up a newspaper to be a huge burden.

As someone who doesn’t have African Ancestry (but is related to people who died in the Holocaust), I use this exercise to help me think about how to teach about slavery and how slavery continues to impact American society today. Were slavery and the Holocaust the same? No. Germany operated concentration camps from 1933-1945 (12 years) with more than a thousand camps across its territories. Slave labor camps operated for nearly four hundred years in the Americas, across a much larger territory. Between 10-20 million African people were abducted and taken to the camps. By some conservative estimates, 1.8 million people died in Africa, 1.5 million died on the voyage, and another 1.5 million died during the first year in the labor camps. Those that lived worked the rest of their lives in terrible conditions (Rediker, The Slave Ship, 6). This number doesn’t even account for the generations of people who lived and died in the camps who were descended from the original captives. My goal here in invoking the Holocaust isn’t comparative suffering, it is empathy. As Erica Layne so poignantly puts it, “Empathy is not a finite resource.”

For historians such as myself who work on Jews and slavery, empathy can seem tricky. After all, once we start talking about Jews owning slaves it can feel like a slippery slope into the 1991 book The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews which argues that Jews dominated the slave trade and which most historians agree is not only inaccurate but antisemitic. Even Henry Louis Gates–probably the most important Black Studies scholar alive–argues that “the book massively misinterprets the historical record, largely through a process of cunningly selective quotations of often reputable sources” (Kepel, Allah in the West, 68–69). Just because Jews weren’t solely responsible for the slave trade doesn’t mean that they never owned slaves or didn’t partake in the triangle trade, however. Most countries in early America were slave societies in which slavery permeated not only the economy but all aspects of life. As Ta-Nehisi Coates puts it early Americans living in slave societies “grew up, were socialized by, married, reared children, worked, invested in, and conceived of the idea of property, and honed their most basic habits and values under the influence of a system that said it was just to own people as property” (“The Slave Society Defined“). Early American Jews were a part of that system. Jews weren’t more responsible than other people for slavery, but they also weren’t less responsible.

For me, teaching about slavery is part of my job as a scholar of early America. Slavery isn’t an “African American subject,” it is an American subject. Most enslavers were white, and hence the responsibility for dealing with slavery and its aftermath is on whites. Slavery has shaped the fundamental beliefs today in the United States about whiteness. To be sure, some American Jews aren’t white and/or have ancestors who were enslaved. But even white Jews need to learn about Jews and slavery. The ancestors of many Jews in the United States arrived in the Americas between 1880-1920 from Europe. Those Jews may feel like they aren’t responsible for slavery, end of story. This passing of the buck, however, ignores the way that American Jews who are perceived as white benefit today from the legacy of the slave system. Thinking about the legacy of slavery today is painful but important. Being honest is crucial to healing.

Here are some key concepts that I emphasize when writing or teaching about Jews and Slavery:

- People who were enslaved weren’t happy about it regardless of who enslaved them (Seemingly obvious, but worth repeating since so much of American popular culture suggests otherwise, including media made for kids).

- Not all Jews came to the Americas from Europe. Many of the people captured and forcibly transported from Africa came from areas where people had oral traditions about being Jewish (See Where We Came from > Western Africa).

- In some places in early America such as Suriname, Jews with African ancestry made up about 10% of the population. They are an important part of the story of American Jewish history.

- Enslaved people brought important cultural traditions with them from Africa that helped create what is distinctive about American culture including art, music, clothing, hair styles, fabric, architecture, religion, and much more.

- While Jews were both enslavers and enslaved themselves, more Jews were enslavers.

- Jews in early America disagreed just like today. Some fought for the rights of people (and Jews) with African ancestry, while others sought to suppress those rights.

- Jews weren’t “better” slave owners than other people. (See previous item. Also really? This is like saying someone was a better Nazi.)

- The goal of thinking about white privilege isn’t to feel guilty, but to work to make the world a better place for everyone. Check out the Reparations Guide from Coming to the Table. These are intended for people whose ancestors owned slaves, but they apply to everyone who wants to heal wounds Some of these suggestions include items you could do with your classroom.

- I am going to mess up some of the time. Messing up is better than pretending to be perfect or ignoring hard to talk about subjects.

Looking for more help? Here are some great books you can use for helping students think about slavery and early America:

- Herron, Carolivia. Always an Olivia: A Remarkable Family History. United States: Lerner Publishing Group, 2014.

- Johnson, Pamela, and Kamma, Anne. If You Lived When There Was Slavery in America. Paw Prints, 2009.

- Carson, Mary Kay. The Underground Railroad for kids: from slavery to freedom with 21 activities. Chicago Review Press, 2005.

- Lester, Julius. Let’s Talk about Race. HarperCollins, 2005.

- Teacher’s Guide: Slavery in New York. New York Historical Society, 2011. [Also the Exhibition]

- Worried about using the wrong words? Check out this resource page of vocabulary and key concepts.

- Resources on Slavery from Teaching Tolerance: A Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center

- Toolkit for Teaching About White Privilege to Elementary School Students

Sounds Far Fetched?

For those who were irritated by my fake teacher and felt no one would ever make those claims about slavery, I offer the following examples:

barely mentioned the Holocaust

- Reiss, The Jews in Colonial America. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers, 2015. Mentions slavery 6 times, slave 7 times in 239 pages.

- Rosenbloom, A Biographical Dictionary of Early American Jews: Colonial Times Through 1800. University Press of Kentucky, 2014. Mentions slaves or slavery 5 times.

- Sachar, Howard M. A History of the Jews in America. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013. Mentions slavery 21 times and slave 13 times in 1072 pages.

referred to them as “detention centers.” In 1959, Stanley Elkins famously made an analogy between Nazi camps and southern slave plantations and specifically attacked the romanticizing of labor camps in the south through the myth of pastoral “plantations.” Yet much of American culture romanticizes plantations today. Consequently, the word is still a subject of much controversy today. The following works use the term “plantation” without comment:

- Faber, Jews and the Slave Trade.

- Feingold, Zion in America: The Jewish Experience from Colonial Times to the Present.

- Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade.

- Marcus, United States Jewry, 1776-1985.

insisted her ancestors who worked at those centers were always kind to Jews. “They were good Christians and gave them Sundays off.” Scholars who repeat or address this myth:

- Faber, Jews and the Slave Trade, 62.

- Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade,

- Marcus, United States Jewry, 1776-1985, 14-16.

- Rosen, The Jewish Confederates, 63.

- Schorsch, Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World, 227-228

plays you some zimrot that Jews sang while they were there. W.E.B. DuBois attacks the idea that hymns are a sign that “life was joyous to the black slave, careless and happy” (“Of the Sorrow Songs“). This was one of the most common interpretations of spirituals throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

They were just bad eggs

- See “The Myth of Robert E. Lee And The ‘Good’ Slave Owner“

- Critical of this story: Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, 24, 75.

- Criticism as a self-serving myth: Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, 60-61.

- The most recent use of this logic was the national security adviser referred to police corruption as a problem of few “bad apples.”